Is Genocide Okay When God Does It?

God commands and commits things we'd consider wrong in any other case. Are they okay because he does them? Within any Christian framework, this question is bound to arise; and too often, it is met with deceitfully dogmatic rejections of God's capacity for wrongdoing. Although these rejections are biblically contestable, they are also biblically supportable. Essentially, God has a perfect plan for the ultimate good; thus any apparent wrongdoing, no matter the degree, must ultimately be good.

Does that mean genocide is okay when God does it? That's a bit of a loaded question, so let's break it down. Before we question God, we must determine whether we even have the right to do so. If that turns out to be the case, the question we're asking assumes that what God is doing appears to be wrong. Who or what defines what is okay and what isn't? First, Christians believe that God himself is a moral standard, which is purported to be invariable; second, there are human moral conceptions, which can be quite variable. If God appears to violate our moral conceptions, must we conclude that his morality is greater than ours? That he has a greater plan which we simply cannot fathom? I am not convinced that we should.

Who are we to question God?

Let's assume that the Christian God is the true one; who are we to question the morality of his actions? He is God, after all. The Bible, however, shows that we do have the right to question the morality of his actions. Abraham, for instance, pleaded on behalf of any potential righteous people within the city of Sodom (Gen 18:23-26). He went so far as to argue that God would not be "do[ing] right" if he killed the righteous with the wicked; and God evidently agreed, saying that he would spare the entire city for the sake of even ten righteous people in it. Interestingly, he did not know how many righteous people there were until he went to see (which contradicts the doctrine of omniscience). In the end, of course, he destroyed the city, which apparently had less than ten righteous people.

Abraham leveled the same accusation as we do today, and what is God's response? He does not tell Abraham not to question him. On the contrary, he concedes to the plea. This raises the question; had there been more righteous people and Abraham been silent, would God have wrongly killed righteous people? It's unclear in this case, since God may have ended up noticing and sparing them regardless of Abraham's intervention.

A similar exchange occurs between Moses and God in Exodus 32:10-14 (as well as Num 14:12-19). Again God listens, and this time, he repents of his wrathful intentions. This shows that not only do we have a right to question God; he can even be influenced by our questioning. Furthermore, Moses asks God a question of particular interest: why would outsiders want to follow a God who had "evil intent that he brought [his people out of Egypt] to kill them" (v. 12)? In reality, the Egyptians' perception of God matters not as to whether he is the true God. If they choose not to follow him, they do so at their own peril. Yet God makes no mention of this fact; instead, he concedes to Moses' plea. The takeaway of this interaction is that even God understands that practical appeal trumps truth in people's decision to adopt a worldview, which leads us to the next premise.

Any worldview hypothesis must appeal to our standards

First, this argument requires some background. Positions in favor of God's omnibenevolence boil down to a set of assumptions:

- God inspired the Bible (2 Tim 3:16)1 and was honest when doing so (Num 23:19; 1 Sam 15:29; Heb 6:18; Tit 1:2). Therefore, there is no reason to question the following two biblically derived premises.

- God's choices ultimately "work together for good for those who love [him]" (Rom 8:28), with the purpose of his commandments being "[our] own well-being" (Deu 10:13). If we observe anything that appears to be contrary to these facts, it is because—

- God is all-knowing (Ps 147:5) and we do not (and cannot) fully understand him (Is 40:28; Ps 145:3) or his perfect plan. (Got Questions)

These a priori assumptions are unfalsifiable, and as such, they form an intellectually dishonest argument. However, the lack of falsifiability does not mean these claims aren't true. Other worldviews make similarly absolute claims, so how do we know which one is true? We'll get nowhere in trying to convert someone by telling them their claim is wrong because our God says so. We need to make some kind of case as to why theirs is wrong; otherwise, it's simply a matter of the tradition in which we were raised.

Although there are many ways to make a case for which worldview/God is the true one, I think there is one method of evaluation that occurs most innately in us—and therefore most frequently, albeit without our awareness. William James (1897) aptly observed that "as a rule we disbelieve all facts and theories for which we have no use" (p. 10). To put it in biblical terms, the method is to observe a worldview's followers and see what fruit they bear. How do I feel when I'm around them? Do their beliefs infringe upon me or other people around me? Does their life look like it has something of value that mine lacks? Do their beliefs appear to facilitate their functioning, or do they hinder it? While this information may not be consciously sought, findings of this nature are, without a doubt, the number one factor in one's decision to adopt a worldview. Once we've made that decision, we continue evaluating all other worldviews in a similar manner—often with the exception of our own.2

Take utilitarianism for example. This worldview posits that "good" is defined as that which brings the most happiness to the largest amount of creatures across the widest span of time (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)—another unfalsifiable claim. It could be true, but we have no means to absolutely verify its truth. In any case, I imagine most would oppose utilitarianism because, when taken to its extreme, it advocates for genocide in the name of "the greater good." Even though that fact has no bearing on whether utilitarianism is true, it's what we innately point to in our opposition. It is on the basis of appeal, therefore, that utilitarianism is rejected.

Perhaps a more familiar example is the religion of Islam, for which many Christians that I've encountered hold a bit of contempt. The idea that the Quran instructs the execution of non-believers strikes fear into us. Our feelings, however, have no bearing on whether Allah, as depicted in the Quran, is the one true God. If he is, it is simply the reality, and we would have to accept it. Let's compare this with the Christian hypothesis. Despite both hypotheses being equally unfalsifiable, Christians stand firm in their belief. Therefore, there has to be more to it than simple evaluations of truth claims. It's crucial to recognize that we evaluate worldviews not by their truth, but instead by their appeal. In Allah's case, we might ask, "how could a loving God command his people to be violent tyrants to those whom they're trying to convert?" Surely such a God can't be the true God; no, a good God is one whose followers exemplify his goodness.

It's important to clarify that such fear of Islam cites misconceptions3 about commands to kill non-believers. Rather ironically, it is the Old Testament God who commanded such despicable acts. Several times in Deuteronomy, God commands Israelites who end up in another religion (i.e., breaking God's covenant) to be put to death (Deu 13:5; Deu 13:6-10; Deu 17:2-7). I suppose that one is conceivably fair, since consenting to (and then subsequently breaking) God's covenant means that they at least had a choice to begin with. No doubt would these commandments be defended by most Evangelical Christians, though I'm sure they're glad that's not how God handles it anymore. What I'm not sure they'd defend is the death-threat conversions that were commanded (Deu 13:12-15; 2 Chron 15:13)—the Old Testament God is guilty of precisely what Christians fear in their misconceptions about Islam.

To reiterate, God understands that this lack of appeal poses a practicality problem for the propagation of his word (see again Ex 32:12-14). What kind of faith does a death-threat conversion even produce? What kind of spiritual relationship is that? It is difficult to reconcile God's often relentless cruelty, even to those who deserve it. This, however, raises another question. Who, if anyone, actually deserves it?

Forgiveness Is Greater Than Capital Judgement

The Evangelical doctrine asserts that everyone deserves to die (Kruger, 2019), and that therefore, it is perfectly just for God to wipe out a people. As can be seen with the pleas of Abraham and Moses, it is not even remotely that simple. On several occasions, God clearly distinguishes between those he sees as worthy of forgiveness and those he will not leave unpunished (Ex 34:6-7). He distinguishes the righteous from the wicked, desiring to spare the former (Gen 18:23-26). Even when God explicitly deems a people as deserving of judgement, he does not always follow through with it (Ex 32:10-14).

Furthermore, if everyone truly met the same criterion to deserve death (Rom 3:23; Rom 6:23), and it were perfectly just to wipe them out, and God were perfectly just, why is anyone alive? Either we are not all deserving of death, or it is not perfectly just to wipe us out, or God is not perfectly just; these cannot all be true at the same time. This is precisely the moral dilemma God encounters upon Moses' plea. Either he kills them for their continued disobedience or he forgives them, giving them another chance for redemption. Only one option can be the morally greater choice, and his decision to forgive indicates that he, at least in this instance, values the latter as greater.

I would argue that, throughout the course of the Bible, forgiveness increasingly becomes one of the most prominent themes. Jesus is, without a doubt, the climax of this development—the fully manifested advocate for redemption and forgiveness. He is shown standing firmly against the capital punishment that God had previously prescribed for certain sins (John 8:4-11). The themes of redemption and forgiveness are not contested by Evangelical doctrine; rather, "the Bible makes much of the patience and forbearance of God in postponing merited judgements in order to extend the day of grace and give more opportunity for repentance; [Ex 34:6; Num 14:18; Ps 86:15 KJV; 1 Pet 3:20 KJV; Rom 9:22 KJV; 2 Pet 3:9 KJV; Rev 2:5; Gal 5:22; Eph 4:2; Col 3:12]" (Packer, p. 165). It would disagree, however, with God's moral development that seems so evident to me, because they believe that "he does not mature or develop. He does not grow stronger, or weaker, or wiser" (Packer, p. 77).

I simply cannot fathom how one could acknowledge these redemptive themes in the Bible and simultaneously fail to see the portions in which such themes are utterly absent. There are countless occasions of capital punishment, leaving the people no chance for redemption nor forgiveness. What's the unchanging standard being enforced here? At what point does a people group become irredeemable? It appears completely arbitrary, fluctuant and dependent on God's mood. His decisions are based not on any absolute standard, or else we wouldn't have seen the change of heart when Moses brought him to repent of his wrath (again, Ex 32:14). What of the people who had no advocate to quell his fits of rage on their behalf? Since we're so far removed from that era, it's easy to be blissfully ignorant of the degree to which that God was a horrific tyrant. But according to Evangelical doctrine, God's character now is the same as it was then, and that is the principle issue I take with their hypothesis.

Discussion

In sum, we do indeed have the right to question God's actions, and he has been shown to repent of his intentions as a result. Second, any worldview hypothesis must appeal to our standards in order to propagate; God understands he is no exception. Third, if we assume God truly is the invariable, absolute moral standard, genocide is either perfectly just or it is not; and God does not stick to one or the other.

So, is genocide okay when God does it? I know which way I lean, but I can't say for certain. To answer in the affirmative would require me to betray my conscience, while answering in the negative would require a worthy alternative hypothesis. Therefore, the only conclusive claim I propose is that it is a valid question to ask—a question whose existence, in my estimation, does not bode well for absolutist Evangelical hypotheses.

If you've made it this far, I would love to hear your thoughts, challenges and all. For now, I will end with another question that I hope to explore in the future. Is it really that difficult to conceive of a God who is not absolutely perfect?—one who is not all-good, nor all-knowing—yet is capable of learning and of growing, and has genuinely had our best interest at heart from the beginning?

References

Clark, M. (2015). Islam: The Quran itself preaches violence against nonbelievers. The Florida Times-Union. https://www.jacksonville.com/story/opinion/columns/mike-clark/2015/02/03/islam-quran-itself-preaches-violence-against-nonbelievers/985431007/

DawahMaterials.com (2017). Are forced conversions & killing disbelievers allowed in Islam? DawahMaterials.com. https://www.dawahmaterials.com/about-islam/70-religious-tolerance-of-non-muslims/166-are-forced-conversions-and-killing-disbelievers-allowed-in-islam

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=3850

Foster, P. (2012). Who wrote 2 Thessalonians? A fresh look at an old problem. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 35(2), 150–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064X12462654

God, Christ, J., & Spirit, H. (a.d.) The Bible.

Got Questions (n.d.). Does God make mistakes? https://www.gotquestions.org/does-God-make-mistakes.html

James, W. (1897). The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York etc. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897 [Pdf]. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/04003036/.

Kruger, M. J. (2019). Is God Guilty of Genocide? The Gospel Coalition. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/god-guilty-genocide

Packer, J. I. (1993). Knowing God. InterVarsity Press. https://www.ivpress.com/knowing-god-1993

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2014, Sep 22). The history of utilitarianism. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history

Footnotes

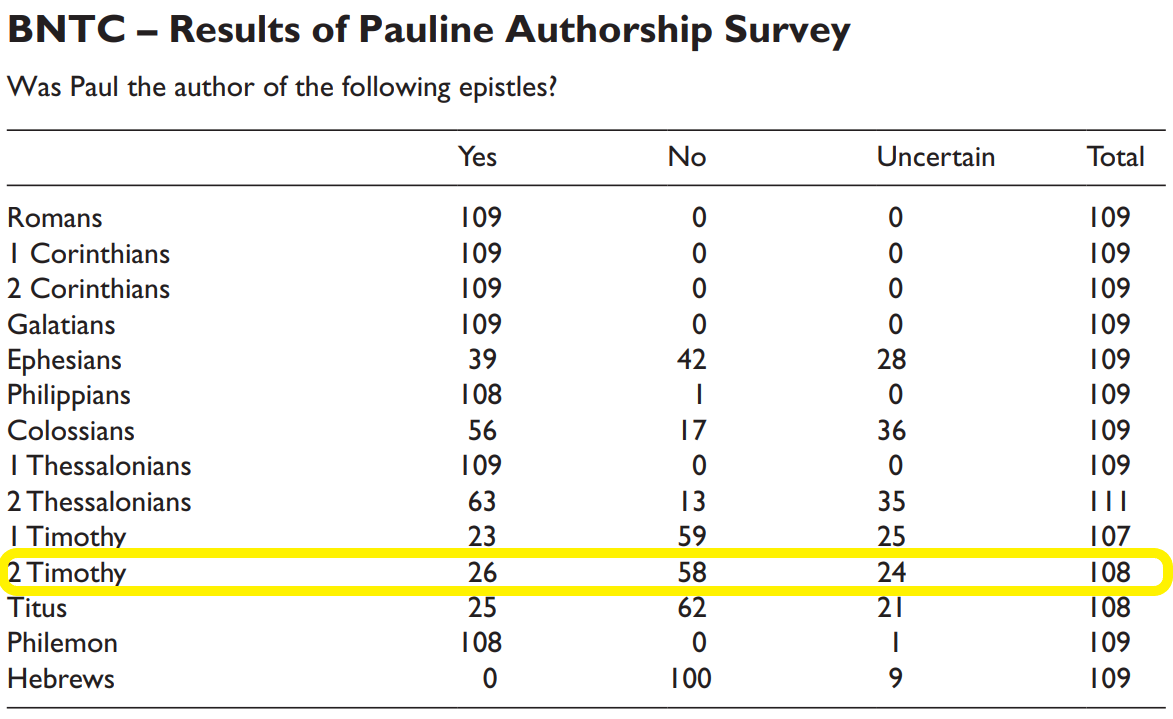

- Interestingly, the only verse in the Bible that claims it to be God-breathed (2 Tim 3:16) is found in one of the books for which many New Testament scholars believe Paul's authorship was falsely claimed:

- Many claim their primary motivation to be truth-seeking, yet will brush aside an astonishing amount of incongruence in order to maintain their beliefs (Festinger, 1957). If truth-seeking were actually the foremost value, Christianity would not have any believers—nor would Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, atheism, nor any single philosophical framework I've encountered, as not one maintains congruency in all its possible iterations. It is for this reason that any genuine endeavor for truth—which does indeed occur—is smothered by the devastating void of solutions. The seeker is left with two options: 1) accept that truth has not yet revealed itself in its entirety, denying themselves the ability to adopt any currently-available worldview; or 2) take on a diluted standard of truth, enabling them to adopt a worldview. Therefore, truth-seeking appears not to be the need being satisfied by our adoption of such worldviews, at least not in an absolute sense. Rather, the worldview must only be true to the degree that it works better than the alternative for the individual.

- The Islamic commandments to kill non-believers are taken out of context (e.g., Clark, 2015), and the Quran's message certainly isn't to force non-believers to convert by threatening death (DawahMaterials.com). The verses' context in the source itself (Surah 2:191; Surah 9:5) reveals quite clearly how misrepresented they've been.

(Foster, 2012)